SAD NEWS

Sad news and a sweet recipe this week. We are making Saba Feniger’s honey cake in her honour, as she passed away in May, aged 92.

Saba Feniger in her Melbourne kitchen, 2015

Saba was another of the wonderful women I have met through this project, and by any standards, she was extraordinary, in fact formidable. Saba was sharp, sharp as a tack, as a knife through butter, when I met her before she turned 90. She was precise, organised, energetic, engaged with life, and with her family, which included 2 daughters, and 6 grandchildren. The last time we spoke she told me proudly that she had also become a great-grandmother, to little Mila.

Saba was the first (voluntary) curator at Melbourne’s Jewish Holocaust Centre when it was established in the 1980s. She painted and was an author. writing anthologies of poems, a memoir, Short Stories, Long Memories, and a historical novel, published in 2016, after she’d turned 90 (!)

Needless to say, Saba was a great raconteur, and at the same time was also interested in others. “Yes, Irris this project is all very well, but is there money for you in it?” she said to me, more than once.

Every time I went to see her, Saba was open and generous. She always invited me to lunch, which she prepared. It was the same kitchen where her writing group gathered, and where we photographed her baking honey cake, with her grand-daughter, Keren Dobia. (recipe below)

Saba Feniger and her eldest grand-daughter, Keren Dobia. Hugging always improves baking results...

Her experiences in the Holocaust, and the terrible losses she suffered never left her, but nor did they prevent her from living the rest of her life. In fact, living large. Saba was a joiner and a doer, volunteering for Jewish organisations throughout her life. She was on the parents’ committee at Bialik College in Melbourne, including working on their cookbook I Love to Eat, part of the team that tested every recipe. Later she worked for years for Jewish Care. The Melbourne Jewish community has lost another titan.

How can I forget? By Saba Feniger

How can I forget that love meant not stealing a sliver of another’s bread?

Sacrifice meant sharing one’s sugar.

How can I forget the sight of my hungry father or the eight watchful eyes measuring every serve?

How can I forget the unspoken decisions -- whose needs were greater?

I survived.

How can I forget?

I nourished my growing body by sapping their shrinking ones.

How can I forget?

family history

Saba was born Saba Davidovicz in Lodz in Poland on 14 August 1924, the protected youngest child in a household of loving women.

“My mother was the oldest of 3 sisters, and she had 3 daughters. And we all lived together. Along with my father.”

Her mother’s sisters were Gucia and Pola. Aunt Pola was Saba's favouite, especially after her mother’s death when Saba was 11 years old. “I adored her and I always wished I would be like her. Pola was elegant and she had beautiful hands and lovely nails.”

I remember that Saba emphasised this with a wave of a perfectly manicured hand. When I commented on her flawless red nails Saba said, “I always try to live up to her standards.” Seventy years after her aunt Pola’s death, Saba had not forgotten her; Pola remained a vivid presence in her life.

Saba's mother (left) and her sisters, Pola and Gucia (seated). Saba's mother died when Saba was 11 years old, and her father married his wife's sister Gucia. Saba loved her aunt Pola the best.

WAR

Saba was 15 years old when the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939.

“No one thought anything so terrible. I heard my father many times talk to my aunt about the First World War. They talked about the Germans being so gentlemanly. My mother and her sisters came from a little town near Lodz, and when the Germans occupied their house they let them live there too. They always were telling us how well they behaved, the Germans. So who would have imagined what was to follow?”

Jews taking their belongings into the Lodz Ghetto, 1940. (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

LODZ GHETTO

Saba spent her remaining teenage years in the Ghetto the Nazis established in her hometown of Lodz. “We had to move from our house in the centre of town into the ghetto and we got one room for 5 people. So it was my father, my stepmother, my Aunt Pola and Edzia my middle sister, and we were all in one room. No facilities, no running water, nothing. We had what could we bring with us, very little.”

The ghetto was sealed off in December 1940, and by December 1941, according to German records there were 163,623 Jews behind barbed wire in an area of 3.8 square kilometers (1.5 square miles). “No one could come in. We had no outside newspapers, we had no radio; we didn’t know what was going on in the world,” Saba said.

Jews moving into the Lodz Ghetto - known as Litzmannstadt to the Nazis. The sign says that entry to non-Jews is forbidden. (Photo: Bundesarchiv)

More than twenty per cent of the population of the Ghetto died from overcrowding, hunger and disease. And yet Saba remembered that time as easier than what followed. “It was easier because we still had a home, we still were together, we still had some food, although it was rationed but there was still a bit of food come in and we worked and we stayed in the ghetto.”

Lodz Jews lined up behind barbed wire, 1941. (Photo:Bundesarchiv)

WORK - CHILDREN

Saba and her sister Edzia worked in the Children’s Colony, looking after children who'd lost their parents. “It was more than an orphanage. They were so many, it was like a colony. And then in September 1942 that work came to an end after the Jewish Ghetto leader Chaim Rumkowski declared that he has to give up the children to the Nazis.”

Chaim Rumkovski, controversial Jewish leader of the Lodz Ghetto, meeting with Nazi officials, including SS Chief Heinrich Himmler (seated in car) Lodz, 5 Jun 1941

Rumkovski's speech to the Jews of the Lodz ghetto, 'Give me Your Children', became infamous. He demanded that people should deliver children under ten and adults over sixty-five to Ghetto authorities, in order to fulfill a Nazi quota, arguing this would save the remainder of the Jewish population. After this speech, 20,000 Lodz children were sent to their deaths at the Chelmno camp. They included the children Saba was looking after.

Jewish children, Lodz Ghetto, 1942 (Photo: Yad Vashem)

“The children were taken away, truckloads of them. I had no idea where they were going. But there was a feeling that there was nothing good. And in fact, because I missed my teenage years, I was still thinking of myself as a youngster and although I was 18, I went and hid somewhere.”

Saba said she had no idea where the children were being taken.

"It was beyond understanding, let alone imagining.”

NAZIS LIQUDATE GHETTO

The detail of Saba's terrible experiences during World War Two reveal the depths to which man can sink, and also what a person can live with and live through. In the summer of 1944, Saba, her sister Edzia and her aunts Gucia and Pola were still alive. Her father had died 2 years earlier of a brain haemorrhage. In August, the Jews were ordered to register for a new work detail. Saba’s aunt and stepmother wanted to hide. But Saba decided to register, fearful of what would happen if German soldiers came looking for them with dogs. She was not aware that the alternative was a concentration camp.

“My 20th birthday was coming on the 14th August, the day we had to register. And I told my aunts if I’m meant to live to be 21, I’ll go to register on my birthday. When they heard me say that they decided to register also. For which I still feel guilty.”

Jews being marched to the Chelmno death camp when the Lodz Ghetto was liquidated in August 1944.

The Nazis liquidated the Ghetto in late August 1944. Rumkovski was among the Lodz Jews packed into cattle cars and transported to the Auschwitz death camp. So were Saba, her sister Edzia and their aunts Gucia and Pola.

Jews being deported from Lodz, 1944. Saba, her sister Edzia and her aunts Pola and Gucia were on these transports. They were taken to the death camp of Auschwitz, in another part of Nazi-occupied Poland.

AUSCHWITZ

On the train, the 3 of them became separated from Edzia. After a long journey in inhuman conditions, Saba and her aunts Pola and Gucia arrived at Auschwitz. There, Saba saw Gucia for the last time at the railway siding at Auschwitz. She was included in the group who were to be killed immediately in the gas chambers. “Gucia probably didn't know what took place there, because I didn't. At least I hope she didn't,” Saba said bleakly.

Saba and her beloved aunt Pola clung to each other. They were in the group assigned to slave labour. In September 1944, after some 2 weeks, they were forcibly transferred again. This time they were taken 600 km north, almost the whole length of Poland, to a concentration camp on the Baltic sea called Stuthoff.

"Death Gate" at Stuthoff concentration camp, Poland.

AUNT POLA

At Stuthoff, Saba's aunt Pola became weaker. “Eventually she begged me to let her sleep on the floor, not on the bunk, because in Stutthoff we had bunks. It was a sign she was giving up on life. I reluctantly let her stay on the floor and then not long after she died," Saba said, looking stricken.

"And we had to lift her body, there was only skin and bones of course and I put her out and put her on top of all the other bodies there. It was dreadful. It was a very emotional moment because I loved her more than I loved my mother. My mother had been sick for a long time and I didn’t have that connection with my mother which I had with her. I mourned her. I was twenty; Pola was in her forties," said Saba.

Barracks at Stuthoff, a death and slave labour camp operated by the Nazis in Poland during World War Two.

EVACUATION

By April 1945, Germany was losing the war. Stutthoff was surrounded by enemy troops on 3 sides, with the Baltic Sea was the only way out. The Nazis put the prisoners on barges and used trawlers to tow them out to sea. On Saba's barge hundreds of men and women, perhaps as many as 1,000, slowly sailed west, in the direction of Germany. There was little food or water.

“So we were there for a week, according to the official papers, and lots of people were drinking salt water and the food of course there was none, so people were dying. Because we came from a concentration camp and how well were we in a camp?" Saba asked, expecting no answer.

ABANDONED AT SEA

"And then on 2 May 1945 it became clear that the Germans had left us. They went off in the trawler, and left us there on the barge, hundreds of people without any means of reaching land!”

The concentration camp prisoners could have easily died there. They were saved by their own ingenuity. Among the prisoners were captured Norwegian soldiers, who collected all the blankets aboard and stretched them out to form a makeshift sail.

“They were very clever. They knew that the prevailing wind might bring us to shore, and they were right. They brought us to what turned out to be Germany, the German port city of Neustadt-Holstein,” Saba said.

The date was 3 May 1945. Adolf Hitler had committed suicide 3 days earlier; Germany would formally sign the surrender 4 days later. The war was nearly over. But when the prisoners struggled ashore, German soldiers were waiting for them.

“So we got off the barge, whoever could. Who couldn't, and stayed, they went up and shot them all. The soldiers stood there with the machine-guns and - ratatat," Saba recalled grimly.

MASSACRE

That was not the end.

"While we stood there on the beach we saw people, prisoners, coming with German soldiers in front and behind, and they pushed them, they forced the people into the water near the barge and machine-gunned them too," Saba said.

Saba remembered that the water at Lubeck Bay was red with the blood of a group of up to 40 prisoners shot there. She said she couldn’t explain why the Nazis spared her group and shot the others. Death was random. So was survival.

WAR’S END

Soon after, the British Air Force began bombing Lubeck Bay.

The concentration camp survivors were happy to see the RAF. But another tragedy occurred in front of Saba's eyes. The RAF was targeting what it believed were boats of escaping Germans, but turned out to be other ships carrying concentration camp prisoners.

More than 7,000 prisoners on 3 boats died, one of the largest maritime losses of the war. And Saba was there, a witness to it all.

The Cap Acona, the largest of the ships bombed by the RAF in Lubeck Bay was a German luxury liner seconded as a naval vessel by the Nazis during World War II. Its final job was carrying concentration camp prisoners. More than 5,000 died on this ship alone.

Saba Feniger was watching from the shore as the RAF bombed the Cap Acona and 2 other ships in May 1945. More than 7,000 prisoners were killed.

"Saba, hide!" a friend yelled, looking up at the British war planes.

But Saba had seen so much death she had become fatalistic. “I said, If it hits me, it hits me, and I didn't hide."

Saba and other prisoners who were still alive left the scene of carnage at the Bay. As they walked up the hill, armoured jeeps appeared on the road ahead of them. Saba noticed that the soldiers were not wearing German helmets. She recalled the sweet moment.

"I asked them in English, Are you American? And they said, No - we’re British!”

FRONTLINE SOLDIER

Here, Saba’s story became entwined with that of one of those British soldiers.

Major Ted Ruston enlisted in the British army during the 1930’s, aged 19, and was a soldier for the whole of World War Two.

Major Ted Ruston and his new wife, Cathy. They married in 1944, the year before he saved Saba Feniger and other concentration camp survivors at Neustdadt in 1945.

In March 1945, he was awarded an immediate Military Cross for heroism during a battle crossing the Rhine River. Two months later, Ruston had led his men all the way north to the German coastal town of Neustadt-Holstein. There on 3 May 1945 he had his first encounter with concentration camp survivors. He was 30 years old and had been fighting for 6 years and he’d never seen suffering like it.

“Walking up the road were these filthy, wet, bedraggled, frightened people. They were filthy beyond words and they’d had the guts and energy to get ashore. They could have been young, but you couldn't tell, they were sorry souls still in concentration camp uniform," Ruston said.

“It was the first time I’d spoken to people in those uniforms, and it was very distressing. They gave us a very effective description and we had no idea that this kind of thing was done. I was livid," Ruston said in an interview he gave to the Spielberg Foundation in 1996.

NEUSTADT HOLSTEIN

Conditions were even worse at the naval base where Saba and the other concentration camp prisoners ended up. In his Spielberg interview, Ruston described seeing German soldiers, and also piles of dead bodies and many prisoners so sick they were teetering between life and death.

“On that first day, the sick ones were lying there in their excreta, they couldn't help themselves, dreadful mess. It made my men very angry,” said Ruston. “There were people everywhere, in concentration camp kit, or clothes they’d just picked up, and all ages, old young, men, women, children, from all over Europe. These people were pushed in there because there was nowhere else to put them. Some had come from Neungammer slave labour camp near Hamburg, others from Stutthof in Poland – including a woman I later met again in Melbourne.”

That of course, was Saba Feniger, who was then 21 years old, ill and as far as she knew, without close family. Ruston outlined the steps he took when confronted by thousands of sick, traumatised people who needed food and a clean, sanitary place to help them start to recover. First, British soldiers had to bury the dead bodies that lay all over the barracks compound.

“I couldn't tell you how many. One hut was full. Lots washed up at sea. It was outside my patch. My job was the living,” Ruston said. “I knew there was typhus in Bergen-Belsen, so we deloused everyone, to get rid of it. That was all on the first day, elementary.”

DAY ONE

Ruston’s most urgent problem was that water, power and sewage had all stopped functioning. The compound appeared to be a naval training base, where the German Navy trained sailors to serve on submersible U-boats.

German U-Boats. The compound at Neustadt where Saba ended up, literally washed ashore after the War, had been a German naval training base.

“I knew that because I’d seen sections of U-boat that you’d only have at a training camp. So I knew if that was so, there’d be a garrison engineer somewhere nearby. I told my Sergeant Major, ‘Take my jeep, take my interpreter, go to the local council and find him.’ Anyhow he came back within an hour with this chap,” Ruston said.

Ruston persuaded the German engineer to return with all the men who had worked there during the war. Then he laid down the law.

“I told them, 'You’re not leaving till everything works again, till the water’s running and the motor generators are working.' So they worked, and I kept them there for 5 days until one said ‘Our wives will be getting worried about us.’”

Ruston called over his interpreter and said that he wanted him to translate what he was about to say very carefully.

‘I said, Look around, you see these people in this dreadful uniform – there are a lot of women all over Europe worrying about them. Don’t tell me your wives are worried because you’re just a few. And your bloody government caused all this.’ So that shut him up. But they all worked very well, as Germans do, and not long later I let them go home.”

A postcard of the town of Neustadt flying swastikas during WWII.

By the time Ruston left Neustadt in 1946, it was a functioning Displaced Persons camp with clinics and bath-houses and vocational training, and it continued working for another 3 years. Ruston had made a major contribution to saving the lives of the surviving prisoners, including Saba Feniger.

SABA AT NEUSTADT

Saba spent around 18 months at Neustadt, trying to recover her health, doing vocational training, and searching for missing relatives. Her father, step-mother and favourite aunt had all died during the War, but she didn't know the fate of her two older sisters.

She was heartbroken to discover that the eldest, Hela, who’d looked after Saba when their mother was ill, had also been killed. SS death squads had murdered Hela along with her husband Benno and their baby boy, Sevek, in their village near Bialystok after Germany attacked Russia in 1941.

Saba's sister Hela, with a friend before the war. This is the only photo Saba has of her eldest sister.

Saba kept searching for her middle sister Edzia, from whom she’d been parted on the journey to Auschwitz. When she discovered that Edzia was still alive, it was a deep and abiding joy. Saba was no longer entirely alone.

Below, Saba (left) and Edzia after the war. Both ended up in Australia.

AUSTRALIA

Saba applied for a visa for Australia. She arrived in Melbourne in 1949 and slowly built a new life. She worked in a factory, and met Sol Feniger, a Polish Jewish immigrant with a similar background to her own. They married in 1955, and had 2 daughters, Helen and Vivien.

“He was also a Holocaust survivor, but we didn't talk about our stories. He was concerned with building a business and looked forwards and not back. Well, we both did,” Saba explained.

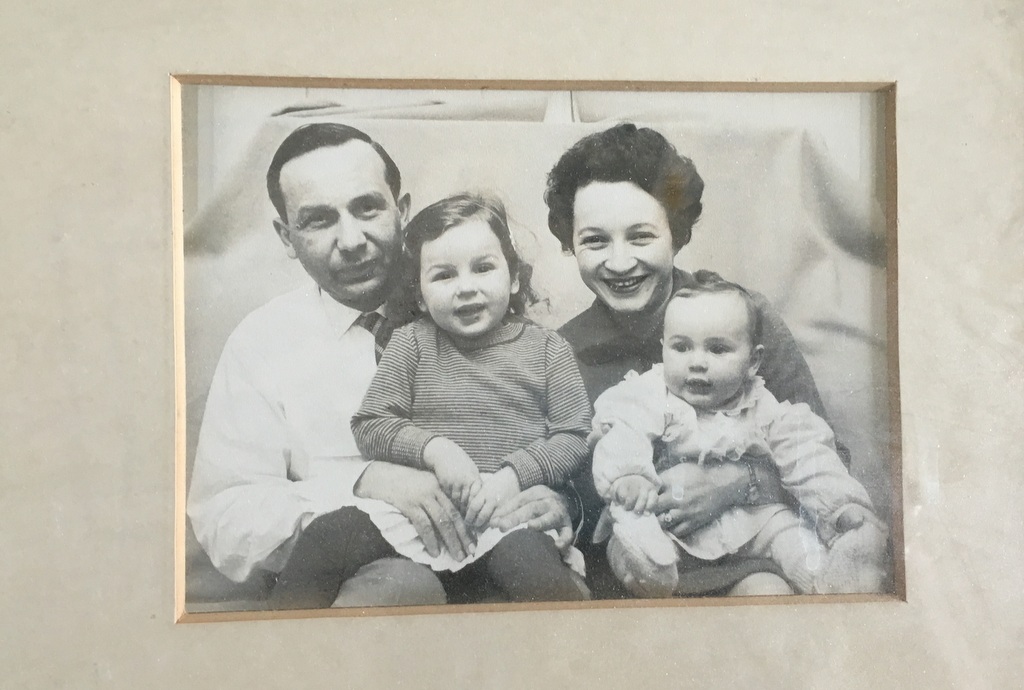

Saba and her husband Sol and their 2 daughters, Helen and Vivien. Sol was proud of his daughters, had a wry sense of humour and did not suffer fools gladly, says Helen.

Saba never really spoke to her husband about his war. "To this day, I don't know exactly what happened to him," she confessed.

It was only after 40 years that Saba was ready to talk about her own experiences. "There’s a Melbourne rabbi who says that you need 40 years to process a trauma - and it was 40 years after the war, in 1984, when the Melbourne Jewish Holocaust Centre was established, and I began working there."

Saba was the Centre’s first voluntary curator and remained for 17 years. And it was through the Holocaust Centre that Saba met Major Ted Ruston again.

REUNION

In 1994, Ted Ruston and his wife Cathy moved to Melbourne, where their daughters now lived. After a life in the military, in business, as a local councillor in the UK, where he also campaigned for war veterans’ pensions, Ted Ruston became an Aussie.

When he visited the Holocaust Centre, he saw a photo of Saba and other survivors, taken at Neustadt in 1946 and instantly recognised the camp he had established. He asked the Centre to send a message to Saba. Fifty years after the War, the two old survivors, now aged seventy one and eighty, met again.

They set a date for Ruston to come with his wife Cathy to Saba’s home. As the 14th of December 1995 approached, Saba found herself excited and anxious.

"How do I address him? What do I do when I see him? The English are very reserved and proper. Do I embrace him? Do I kiss him? So I politely shook hands," Saba recalled.

In many ways, the two were peas in a pod -- intelligent, principled, self-possessed, and profoundly affected by their (very different) war time experiences.

“He brought his photo album and I opened my photo album and we compared notes,” Saba said.

The meeting which Saba described as "unexpected yet unforgettable", also provided her with a measure of relief. "He saw us. He is the confirmation of my memories," she said.

After that, they exchanged cards at Christmas and on birthdays and of course on the anniversary of Saba’s liberation. The two families met every year on that date to celebrate her survival.

"He gave me my life back," Saba said simply.

In 1995, 50 years after World War Two, Saba Feniger meets her liberator, retired British Major Ted Ruston. They compare notes and photographs in her Melbourne home.

EULOGY

Ted Ruston died on 30 December 2014, aged 99. Saba Feniger who was an underweight prisoner hovering between life and death in 1945, outlived the soldier who liberated her. She attended his funeral, and delivered a eulogy, which had everybody in tears.

“Ted, my saviour, was larger than life and I was in awe of him and of his passion for life. I felt his deep affection toward me and my whole family. I knew that it was as important for me as it was for him to recall the liberation," Saba said at the church.

Major Ted Ruston, 1915- 2014

Just over 2 years later, in May 2017, Saba also passed away. Her daughters and Ted Ruston’s daughters, who all live in and around Melbourne, now share a life-long bond forged by the deep connection between their parents.

May both Saba Feniger and Ted Ruston rest in peace.

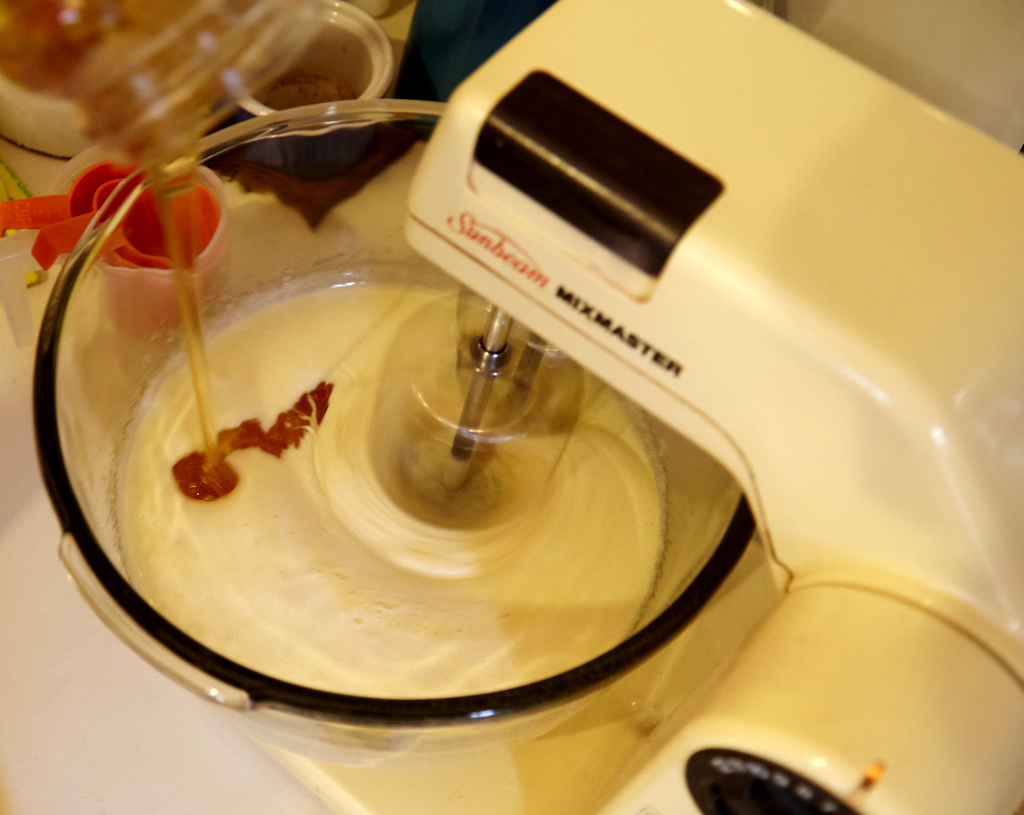

HONEY CAKE

After that extraordinary life story, full of suffering, but also love and intense connection, it's definitely time for a cup of tea and a piece of cake.

This wonderful moist dark honey cake was one Saba's favorites. It's still so hard to write in the past tense. I wrote "is" and had to change it, something I've been doing throughout while writing this. I simply find it hard to believe that Saba, with her humour, energy and forcefulness, is no longer with us. Her daughter Helen says, "We miss mum every day."

Saba included this cake in a collection of family recipes which she made up for her grand-daughter when she got married. She said it was a very forgiving recipe. You could add alcohol and nuts or raisins. Or not. You could add spices. Or not. Somehow, the recipe will always work and the cake will always be good.

Saba baking with her grand-daughter Keren Dobia.

Saba’s Dark Honey Cake

INGREDIENTS

- 1 cup boiling water

- 3 tea bags

- 2 eggs

- ½ cup brown sugar

- 1 cup honey

- ¾ cup oil

- 1 cup self-raising flour

- 1 cup plain flour

- ½ teaspoon bicarbonate of soda

- 1 tablespoon Nescafe or cocoa

- 1 tablespoon of mixed spices - cinnamon, nutmeg, a little cloves, a grind of black pepper

- OPTIONAL - 3 tablespoons rum - handful raisins or walnuts

METHOD

1. Make one large cup hot very strong tea, with the boiling water and 3 teabags. Set aside to steep.

2. Beat sugar and eggs till pale and fluffy, then add oil and honey and beat well. (Tip: Use the same cup for the oil and the honey. Do the oil first and then the honey will slip right out.)

3. Sift in flours, bicarb and spices and mix well.

4. At the end, pour in the cup of tea. Melt the Nescafe in a tablespoon of hot water and add it here too. The mixture will be runny!

5. Bake in a circular cake tin, minimum 24 cm, or a large loaf tin. If your cake tin has a removable base make sure it fits tightly, or it may leak.

6. Bake at 180 degrees for 45 minutes (sometimes a little more, depending how hot your oven is.)

Best eaten with a cup of tea, listening to Saba tell you a story.

Saba Feniger, 1924-2017. Rest in peace dearest Saba. May your memory be a blessing.