EVA GRINSTON

Eva Grinston is gracious, lively, fascinating and energetic. She lives in Sydney, Australia, mother of 3, grandmother of 4, friend to many, many more. Originally from Bratislava in what was then Czechoslovakia, Eva is a sublime cook (and like many Czech women, a stellar baker).

She follows the news, looks after older relatives, gives talks at local high schools, attends lectures, concerts and theatre. Many women in their forties would envy Eva’s energy levels in her eighties!

FAMILY STORY

Eva was born in 1929 in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, the daughter of Arthur and Elisabeth Silberstein.

She had a younger sister Vera, 18 months her junior. Strong-willed and self-assured. Vera was her playmate and also her inspiration, for although Eva was older, she felt herself to be more timid than her cheeky sister.

Eva was ten years old when World War II began. The Nazis didn't immediately occupy Slovakia, where she lived, as it was ruled by a Nazi aligned government. They created a Jewish ghetto in Bratislava, and in 1941, Eva and her mother and sister were transferred there.

They all survived until 1944, when German troops did finally occupy Slovakia. Eva and her sister Vera, then aged 15 and 13, were deported to the death camp of Auschwitz in Poland. Only Eva survived, Her mother, her aunt and little sister Vera died there.

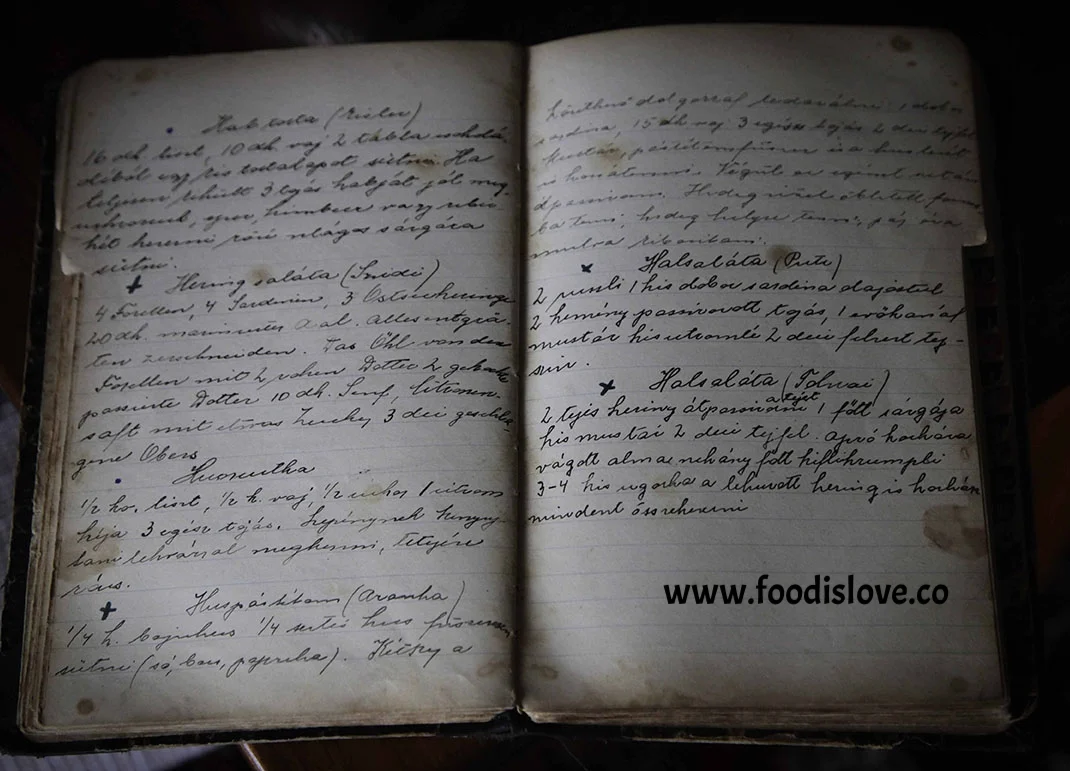

Granny’s cookbook. The recipes are in German and Slovakian. Eva has translated them.

cookbook

After the war, when she was sixteen years old, Eva returned to Bratislava. Weakened by typhoid, bereft, Eva wanted some sense of home. She found Russian soldiers billeted in her family house. They gave her 15 minutes inside.

“You can take whatever you find!”

Eva found that very little remained from her family’s years in the house. In the basement she found a box where her mother had hidden a few family treasures – there were books, photographs, a kaleidoscope Eva had played with as a child, which had been a present from her beloved Granny.

There were the last drawings made by her sister Vera before they were deported to Auschwitz. Eva also found her grandmother’s cookbook. The recipes are in German. Eva has translated them.

Drawings by Eva’s sister Vera who died in Auschwitz, aged 13.

“I asked if I could wander around the house. I sat on a bench where as a little girl I had observed life as it was then and lifted my kaleidoscope to the sky. The day was grey. The kaleidoscope was still working, and I saw the images of my happy early life. I saw Granny, all the members of my family, I saw the faces of the ladies who visited Granny, and the children I played with as a child. My face was wet with tears. I had no hanky. I opened the cookbook and there were the recipes of my Granny, and Granny’s friends.” It was the taste of a vanished world. Over the years, in Sydney, Eva has made almost every recipe including her delicious chicken schnitzel.

BRATISLAVA

The Bratislava that Eva knew as a girl before the War was a cultured, wealthy town, with museums, theatres and art galleries. Vienna, one of the great world capitals, was only an hour away by train. Her family felt they were living in the centre of Europe.

“I was born into a life of love, culture and comfort. Bratislava had it all: beauty of nature, baroque architecture following on from its neighbour, Vienna.”

Sachertorte

“I remember a trip by tram to Vienna with my glorious Granny, to hear my first performance of the opera Carmen,” Eva recalls, “with afternoon tea at the Sacher Hotel to follow! A dream…”

The Sacher hotel was home of the famous Sacher torte, with its layers of rich chocolate and that defining whisper of apricot jam. Cafes, then as now, were meeting places, where people sat, drinking strong coffee and eating impossibly rich cakes, watching the world go by.

Pre-war harmony

Eva describes her family as well-off, though not wealthy. They owned an apartment building in the centre of town. Eva and her little sister Vera lived with their parents on the top floor, and their grandmother lived beneath them with her two unmarried daughters. The aunts spoilt the girls.

Below them, were tenants of different nationalities, German, Austrian and Hungarian, living in harmony. Eva describes the different characters.

“There was a retired Army Colonel, who was Hungarian. He would check the gardens surrounding the house, and report on how many cherries were missing off the tree, or if the strawberry bed needed feeding, with as much care as if the property belonged to him. There was a German-Austrian widow, whose two daughters were musicians. After my Grandpa’s death, she asked my Granny to concerts in her apartment. The janitor, who was German-born with a Hungarian wife, lived in a separate cottage on the premises, and adored our family.”

Later, during the War, he would step in to help Eva and her sister, hiding them from the Nazis at great risk to himself.

Afternoon tea in Bratislava

But before the War, it was a happy life. Eva’s fearsome and beloved Granny held formal tea parties for her friends. Baking went on for two days before they arrived; linen was starched and silver polished. When Eva was 5 years old, she was allowed to attend her first afternoon tea, but only on condition that she would maintain the standards of behaviour Granny expected, including curtseying to the guests, sitting utterly still, only speaking when spoken to, and watching as the invited ladies drank their tea and ate their cakes.

Her reward at the end: a piece of each of the delicious cakes the ladies had been served. But she had to eat in the kitchen, with Lina the cook, so she wouldn't make a mess on the white tablecloth.

Eva's grandmother's Chocolate, walnut and sour cherry cake is now a family favourite here in Australia. It's on the table at every grandchild's birthday, baked by Eva, and symbolising the continuity that is so important to her.

After being featured on the ABC Compass programme, The Taste of Memory, this recipe has been copied more than once!

World War Two begins

When Eva was 10, this world was turned upside down by the outbreak of World War Two.

“All the calm and tolerance, the peaceful life came to an end. My father’s best friend, the bank manager, who always asked us for Christmas dinner, no longer invited us. My mother’s dearest friend came to tell us, tears in her eyes, that we were not to come to visit her any more, as her husband had become a Nazi. My friend Katie looked away in the street when we met. Slowly the serpent raised its ugly head, invaded all, everywhere.”

No Jews!

It began with the cafes. They were declared out of bounds for Bratislava’s 70,000 Jews. The days of sitting and watching the world go by ended abruptly. Schooling also stopped. Eva was a keen student who had just begun secondary school when she was prohibited from continuing her education.

Father

Eva's sister Vera and her mother Elisabeth

Arthur was sitting with his family at the Passover table in April 1939 when there was a knock at the door. The family made jokes about Elijah – for whom Jews traditionally leave a seat vacant at the festive dinner, in case he comes to eat.

Instead, the caller was a friend from her father’s office, who came to warn Arthur that politically active men were being arrested, and that he was next on the list.

Eva’s father departed quickly. There was barely time for a proper farewell.

He expected to be gone two weeks. He was away for seven years.

Eva’s mother, Elisabeth, was left by herself to fend for her two small daughters as the Nazis overran Europe. Eva

Ghetto

After two years of restrictions, including being forced to wear a yellow star identifying them as Jews, Elisabeth and her 2 daughters were moved out of their home into a ghetto. As in other parts of Europe, it was an area where only Jews could live.

In 1942, deportations began. People were being taken away from the Bratislava ghetto in trains. No one knew the destination, or what happened there. But those who remained behind knew was that it must be bad, for nothing was heard from them again afterwards.

Then after hundreds of Jews were deported, the trains stopped. When the Nazis occupied Slovakia in 1944, the deportations resumed. Now there would be no halt.

By then, Eva’s mother Elisabeth was frantic with worry.

Hiding

In late 1944, she arranged to hide her daughters, to prevent them being taken in the next deportation. The janitor from the family’s apartment volunteered, a heroic act, since if they were discovered he could be killed.

“It was a sign of his deep feelings for my grandparents,” says Eva.

Eva and Vera aged 15 and 13, were now separated from both their parents. They spent days together in the janitor’s home lying under a duvet, so that no one looking in would see them. Their mother was in hiding with her sister at another location.

Vera

Thirteen year old Vera was a sunny natured, confident tom-boy, her father’s naughty favourite, and still a child. She had dreams of leaving Europe and going to found a Jewish home in Palestine, a passion she shared with their father.

“She was a brave little girl,” Eva says. “One day, the three of us - me, my mother, and Vera - were out walking together when a man from the Hitler Youth spat at us. He knew we were Jews because we were wearing the yellow star. And, instinctively, Vera spat back. Then my mother did too. I couldn't believe my lady-like mother did that. But Vera did it first. She was extremely able to hold her own.”

The sisters were huddled together in hiding for weeks, talking and playing imaginary games, to combat the fear and the boredom.

Then just days after they heard that their mother and her sister were taken, in October 1944, the girls were discovered by German soldiers. She suspects they were betrayed by neighbours. The two girls were taken back to a collection point for Jews, familiar to Eva since it was near her old school.

They were even relieved to be caught, Eva admits, because they thought it meant they would see their mother again.

But that didn't happen. It couldn't.

Their mother Elisabeth had been captured two weeks before the girls and sent to the death camp of Auschwitz with her sister, Susan. The two women had been killed on arrival.

Auschwitz

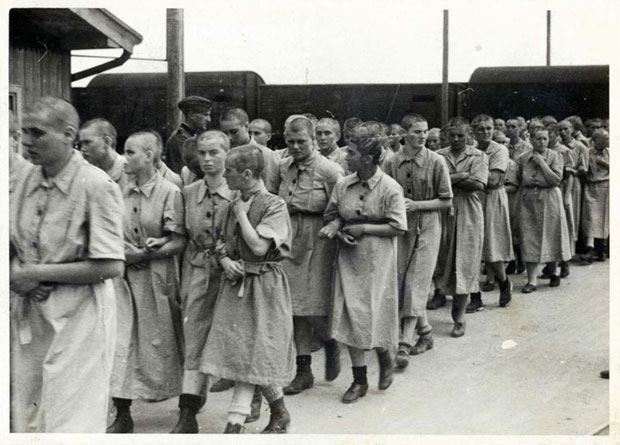

Eva and Vera were herded onto a cattle-train with hundreds of other Jews. They didn’t know where they were going. After four days without food or water, the girls arrived at the same deadly destination: Auschwitz.

The Jews were pushed out of the cattle cars into mayhem. Thousands of prisoners, men and women, old and young, sick and strong were surrounded by armed soldiers with dogs.

The girls looked for their mother. She was nowhere to be found.

Instead, the only person waiting on the platform was a dark-haired German officer, Dr Josef Mengele.

The infamous Nazi was a medical doctor, an SS officer, and a sadist.

He was supervising the ‘selection’ of the new arrivals, determining who was to be killed immediately and who could do forced labour, and would be killed later.

When he saw the two sisters, he indicated they should part, sending Eva to one side and Vera to the other. The girls were only 18 months apart in age, but at fifteen, Eva was already a young woman, tall, diffident and beautiful. Vera still looked like a child.

Eva refused to let go of Vera’s hand.

““I had no idea what was waiting there, not a clue, but I just knew that we shouldn’t be separated, especially so soon after being parted from our mother,” says Eva.”

Dr Mengele shouted at Eva to let her sister go, but Eva held tight to Vera. He stopped, and asked Vera how old she was. She told him the truth.

“Thirteen,” she said.

He spoke to her softly, directly. “You are young. You want to go to school, don’t you? I know what you really want. You want to go to Palestine!”

It was diabolical intuition. There was nothing Vera wanted more. He had given voice to her dream.

"She really thought she would see her dad... " Eva trails off, unable to finish her sentence.

Vera dropped Eva’s hand and ran off - to her death.

There was no goodbye. The final image of the back of Vera’s head disappearing into the line on the other side of the platform has haunted Eva ever since.

“My mother held onto her sister, and I did not hold onto mine,” Eva says sadly.

She has never forgiven herself, though no onlooker could see it as in any way her fault.

SLAVE LABOUR – DAIMLER BENZ

After 3 months, Eva was transported from Auschwitz to Berlin. The tide of the war was turning against the Nazis and they spared Eva and some others to work as slave labourers for them, making weapons.

Eva was taken to the Daimler Benz factory in the German capital, to work on aircraft engines. They toiled underground, never seeing daylight. Food was poor, and conditions difficult. They heard the Allies bombing Berlin above their heads.

By war’s end, Eva was barely alive.

Ravensbruck

As the Allied ground forces closed in on Berlin, German soldiers took their female prisoners to the Ravensbruck concentration camp, and abandoned them there when the war ended.

Eva, stricken with typhus, was too sick to flee.

Russian soldiers liberated her and the other sick prisoners. One bandy-legged Russian soldier, in point of fact, who discovered them, lying there, near death.

“You call these women?” he said, surveying the stick figures on the floor with horror.

The Russians nursed Eva and the other women back to health. After the war, Eva learnt to speak Russian, in tribute to the men she calls her saviours.

Post-war

According to the 1940 census, there were almost 90,000 Jews in Slovakia. It’s estimated that by 1945, only 30,000 remained alive. Two thirds had been killed. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007324

It’s an even higher proportion if you calculate the numbers as a percentage of those who were taken by the Nazis: Slovakia deported 70,000 Jews to Nazi control in the East – including Eva and her family. Of those 60,000, or 85% did not return. Eva was one of the lucky few, but the experience had been so harrowing that she wanted a new life, as far away from Europe as possible.

AUSTRALIA

At 21 years old, Eva migrated by herself to Australia.

On the boat coming to Australia, she met Ibi Wertheim, another Czech woman with a similar background, looking to make a new life. They've been friends ever since.

They arrived on a Thursday - Australia Day 1950 - and had a job the following Monday. Eva wasn’t a skilled worker, but that’s how things were in the Australian job market then.

“I began my love affair with this country from that moment,” says Eva.

In Sydney, Eva worked at various jobs in the fashion industry. She met the love of her life, Michael Grinston, at a party which she had tried to wriggle out of attending. Fate had other plans for her. Good plans, this time.

They married, and brought up a family of 3 accomplished children. Eva now has 4 grandchildren.

Eva has always cooked the European Jewish specialties from her Granny’s cookbook for her family, first for her children and now her grandchildren.

They have all revelled in cakes dense with chocolate and almonds; or rich buttery apple or plum tarts, or more Australian hybrids which Eva has invented - including a chcoclate biscuit, and jam layered ice cream cake of which there is never a crumb left over.

There is always cake on the table when you go to visit Eva, or she will bring a freshly baked offering over to her daughter’s home, where it will be gobbled up.

Memory

Eva always carries the shadow of her war time experiences and losses. There is also the permanent reminder tattooed onto her skin. Inmates in Auschwitz were tattooed with a number on their forearms, and were referred to by that number. It was to track them and also to remove their identity. They were a number and no longer a name.

But once the War was over, eVA made a commitment to reconnect to life.

Every year on 6 May, which is Vera’s birthday, Eva raises a toast to her feisty, passionate little sister, and tries to imagine what she would have been like, had she too survived.

Eva gives talks in Australian schools, about the importance of extending a hand to all new immigrants, and to recognising the humanity of other people, even those who look and sound different from you.

“This is my victory. My long, healthy life. These wonderful children, and grandchildren, brought up here, breathing free air, far from the traumas of my childhood.”

When life gives you lemons and cumquats, make cumquat marmalade! Add star anise, cardamom and orange flower water and the result is warm, spicy and wonderful. Or mix it up with different spices and a little alcohol - you won’t be sorry!

Fancy summer in Jerusalem? in beaugiful historic Ein Kerem. in fact? try here …

What’s FB got to do with a Mediterranean recipe for vegan stuffed veges? You’ll find the whole story here, along with a wonderful tale of love and luck in post-WW2 USA, with a chance meeting on the Brooklyn train. Happy Passover and Happy Easter!

Two fab apple cakes for a sweet New Year. Simple lockdown-friendly recipes that you’ll make again and again. Wishing you all a happy healthy new year, and certainly a better one than the last!

It’s such a simple and delicious thing, so I’m responding to requests for recipes for Latkes by providing 3 different ones for this holiday season. The Jewish festival of Hannukah is the time to fry, baby, fry and to let the light in. Potato, carrot and sweet potato. Go on - have a go! Happy Holidays.

The amazing WW2 survival story of Agi Adler, may she rest in peace, who passed away this year. Archive photos and in-depth interviews about her life in Budapest before and during the war. Along with a recipe of course - the Hungarian potato bake Rakott Krumpli, the ultimate comfort food.

Quarantine Passover means making your own matzo balls - and chicken soup. Here are failsafe recipes for what is likely to be your smallest seder night, when you will have to make most dishes by yourself… matzo balls for anyone who’s never dared to make them before!